I posted this item in December 2015 after some data on physiological testing of Chris Froome was made public in a mostly PR piece. Have a read there first if you haven't already done so.

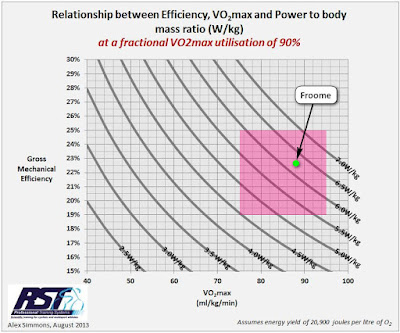

Today I saw the published science paper was released and from the abstract I pulled out a few extra pieces of information, namely Froome's gross efficiency (23% at ambient conditions), power at blood lactate level of 4mmol/l (419W). His reported weight for the test was 71kg, which is likely above his racing weight.

So I thought I'd do up another chart, this time fixing the gross efficiency and VO2max values, and plotting the curve of aerobic power in W/kg terms versus fractional utilisation of VO2max:

The relationship between aerobic energy yield per litre of oxygen, gross efficiency, VO2max, fractional utilisation of VO2max and power output is outlined in this earlier blog post.

So what can we make of this?

1. A TdF winning cyclist has the physiology you'd expect of a TdF winning cyclist. That should be hardly surprising.

2. Froome has both high VO2max and high gross efficiency, which is a killer combo. Neither represent out of this world values. What that means is Froome's sustainable aerobic power output is then a function of his fractional utilisation of VO2max, and FUVO2max at threshold is a highly trainable aspect of one's fitness, more so than gross efficiency or VO2max.

3. The sustainable power as measured in this test was at a blood lactate level of 4mmol/litre, which is an arbitrary level for such testing. What any individual rider's BL level is at their actual "threshold" is quite variable, often somewhat higher.

4. It would seem that Froome's fractional utilisation of VO2max at this power level was ~86-87%. That's a pretty reasonable value for longer duration efforts of at least an hour for highly trained cyclists and it can quite feasibly be higher than that at threshold power, and certainly higher over shorter durations, e.g. 15-20 minutes.

5. The testing was also conducted at high humidity (60%) and temperature (30C) and somewhat interestingly Froome's gross efficiency was higher (23.6%) than when tested at ambient temperature (20C) and humidity (40%). That would add ~0.15W/kg at threshold, a very handy result for hot days. The reported his sustainable power was 429.6W at high humidity and temperature versus 419W at ambient temp and humidity. That power difference of 10.6W / 71kg = 0.15W/kg.

6. Weight. I'd expect Froome's race weight would have been a few kgs less than at the time of testing. e.g. 67kg at same power would add 0.35W/kg to threshold power.

Doping? Once again, this sort of data tells us nothing about any rider's doping status.

Read More......